CS.2 “Printemps des Poètes” and “Morley Literature Festival”

Introduction

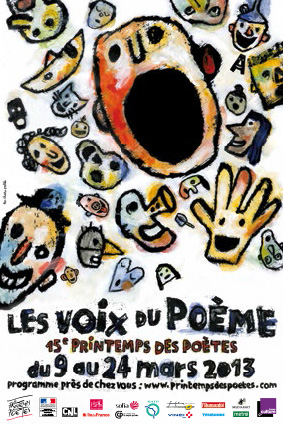

Poster for Printemps des

Poètes 2013

© Printemps des Poètes

Taking the nine questions of this publication as a point of departure, this comparative analysis will discuss primarily the targeting strategies and forms of collaboration with various interest groups associated with the two projects. The nine questions will not all be addressed at the same level of detail or in the sequence in which they are presented in this publication. Instead, the analysis will concentrate on questions that allow a reflection of the mediation strategies and concepts used by the festivals’ initiators.

Printemps des Poètes, France

→ Le Printemps des Poètes, is a French poetry festival that has been held each year in March since 1999. It now involves up to 8,000 poetry-focused events, which take place throughout France. The festival is organized by an eponymous umbrella organization which operates throughout the year at various levels, whose mission is to reinforce the position of poetry in France. Its activities concentrate on the dissemination of poetry-related information through network-building, advisory services and support for the implementation of projects and events. The organization functions primarily as a catalyst for implementation of projects in various contexts: schools, cities, libraries and public spaces. Its website serves both to communicate information about “Le Printemps des Poètes” activities and as a platform for the distribution of poetry-related materials, which is why its organizers call it a “resource centre for poetry”. In addition to presenting dossiers about poetry, book recommendations and notices about interesting events, the site offers access to the following databases:- “Poétèque”, which contains bibliographies, news and extracts from poems from almost 850 poets and presents 533 poetry publishers (publications, collections, contact information) and 4,070 references to works (anthologies, books, journals, CDs and DVDs).

- A poem database with 576 poems, which can be downloaded.

- A yearly calendar of poetry events: readings, performances, festivals, exhibitions, etc.

- The section “OùQuiQuoi?” [Where,Who,What?], presenting events, organizers, poets, publishers and booksellers by region.

Morley Literature Festival, England

© Morley Literature Festival

Discussion

Who “does” Cultural Mediation?Who started the festival and with what intentions?

Why include cultural mediation?

What rationale is put forth for holding the festival?

“Le Printemps des Poètes” was initiated in 1999 by Emmanuel Hoog, André Velter and Jack Lang, one of the founders of → Fête de la Musique [Festival of Music], which served as its model. All three founders were active in the arena of cultural policy and had themselves engaged in the production of culture. Emmanuel Hoog worked for the culture ministry, as a theatrical director and as a consultant to the government in the area of culture and the media. Before becoming the president of the French news agency Agence-France-Presse, AFP, in 2011, Hoog had directed the media archive “Institut National de l’Audiovisuel” (INA). Over the course of a long political career, → Jack Lang had served as minister of culture, communication and education and had been a close adviser of François Mitterrand. André Velter is a French poet, who experiments with improvised songs and “polyphonic poetry”. Working with France Culture, the radio broadcaster, he created → Poésie sur Parole [Spoken Word Poetry], a regular event which combined contemporary poetry with dance, instrumentalization or performances and thus conveyed poetry as a “performative, active and oral medium”. Thus “Le Printemps des Poètes” was the creation of influential cultural practitioners and politicians, who were able to anchor it in the country’s cultural policy and grant the project an accordingly high status in the cultural landscape right from the start. Since 2011, “Le Printemps des Poètes” has been headed by → Jean-Pierre Siméon, a poet, novelist, playwright and critic. Siméon also served for many years as a professor of modern literature at the teacher training institute in Clermont-Ferrand (Institut Universitaire de Formation des Maîtres) and has published extensively.2 He, too, was active in the cultural policy arena, having served as an advisor on art and culture to the Ministry of National Education. Thus Siméon possesses expertise in cultural and educational policy as well as artistic expertise. “Le Printemps des Poètes” therefore continues to be well established with France’s → cultural and educational policy. Accordingly, it receives funding from the → cultural ministry, the → National Book Centre, the → education ministry and the → Regional Council Île de France and it adheres to a logic anchored in the thinking of those bodies. Currently, debate about education policy in France is being influenced by school system reform (→ Refondons l’École de la République3) aiming at the gradual transformation of current teaching and learning practices from four approaches: “school success for all”, “pupils at the heart of the reform”, “well trained and certified staff” and a “fair and effective system”. In this context, “cultural, artistic and scientific education for all”4 is identified as a method of establishing the school of the future.5 Cultural mediation is framed as a practice that improves the level of → individual performance, “supports, promotes achievement and contributes to self-esteem”6 and, finally, can contribute towards equality of opportunity. French cultural policy in the 2012 – 2014 legislative term also calls for the “democratization of culture” and the promotion of access to artistic works and artistic and cultural practices, as well as recognition for a great many forms of artistic expression. In this context, the role of public education and its beneficial effects on local contexts and social change are emphasized, with reference to the basic right to education and the → Law on the Fight Against Exclusion (→ Text 3.RL) adopted in 1998. This approach follows to some degree from a rationale for the support of art and culture based on its beneficial effects on the evaluation of → society and education policy. It also associates itself with the → inclusion debate. That debate, guided by ethical principles and the idea of democratization as promoting of a more just society, is a response to the fact that large parts of the society are excluded from education, culture and politics. In this sense, cultural mediation is supposed to contribute to greater participation on the part of groups which have been excluded thus far from societal processes, and particularly in the art and culture of the majority society. However, the notion of creating inclusion by creating offerings for “excluded” groups fails to address the fact the fact that it is the prevailing conditions which gave rise to these exclusions.7 The Morley Literature Festival is directed by Jenny Harris, a → freelance creative producer and musician, who previously worked for the Leeds City Council as a music officer, in which capacity she initiated the “FuseLeeds” Festival for contemporary music, among other things. She is a co-developer of “imove”, a cultural programme for Yorkshire 2012 and of “the hub”, an organization for cultural producers and people active in the creative industries, which also developed the festival → Phrased & Confused, which combines music and literature. Reflecting a self-declared interest in “inclusive arts practice”, she also coordinates the programme for the Leeds educational network “Arts & Disability” and thus has a structural link with the city‘s cultural and educational policy affairs. The literature festival receives funding from several different institutions. Some of the funding comes from the City of Leeds’ → Leeds Inspired programme, started in connection with the 2012 Olympic Games, which promotes art, sports and cultural events, in order to ensure that Leeds has a diverse cultural programme. According to the Leeds Inspired website, it funds community and DIY projects as well as larger-scale annual events. This represents an attempt to integrate practices primarily associated with political activist circles, such as DIY, in funding contexts. The Morley Literature Festival is also supported by the → Arts Council England, the → Morley Town Council and → Welcome to Yorkshire (the region’s tourist board) and certain businesses, including a → shopping centre, the → Blackwell chain of booksellers and the local press. Thus the project’s funding structure is modelled on a → public-private partnership, a form of partially public, partially private funding that became very widespread during the “New Labour” Government of Tony Blair and has also been growing more common in the German-speaking region since 2000. This mixed financing model serves to shore up overstretched public budgets with private investment. In return, the investors have a voice in the projects they help to support. The model is frequently used to finance school and roadway construction projects, but museums and cultural projects also use it. The model is beginning to appear in Switzerland too, though it remains relatively rare.8 The main critique of this form of financing relates primarily to the increased influence of private funders on political decision-making and thus the risk of a stronger market-orientation in public investments. Another point of criticism relates to the short-term nature of the budget relief: by shifting the investments to long-term partnerships, the public coffers contribute mainly in the form of rents which are paid out to investors over a term stipulated in advance. In the end, this financing model is often financially advantageous to the investors while failing to deliver real public cost-savings over the long run.9 In the case of the Morley festival, it was not possible to ascertain how the selection of activities and the concept of the festival may have been influenced by private funding sources. However, the festival’s programming displays a strong book-market orientation and thus appears to cater to the presumed → interests of the audiences. For instance, participating authors and the patron appear to be selected based on their market position. The festival’s patron is Gervase Phinn, the bestselling author of many books, including several children’s books.10 Phinn also teaches literature at English universities and has served as the president of the UK’s → School Library Association. His academic publications include texts like “Young Readers and Their Books, Suggestions and Strategies for Using Texts in the Literacy Hour”11, in which Phinn advocates new formats of literature education in schools. Thus he is associated with the content and practice of literary education in addition to acting in a promotional role for the festival by evoking a high level of audience interest. Since their resources are concentrated on a single period of time, as dictated by the festival format, both literature festivals are part of the trend toward “festivalization”12. While “Le Printemps des Poètes” organization attempts to use the festival to achieve visibility for activities which take place throughout the year, as a sort of → marketing tool for its own purposes, the festival in Morley operates to a greater degree as a form of local marketing intended to increase the town’s appeal as a destination and to involve the local population.

How is Cultural Mediation Carried Out?

Focus on school partnerships In line with the most recent school reform guidelines, “Le Printemps des Poètes” underlines the complementary nature of cultural mediation vis-à-vis schools and recommends that school curricula take it into account. It advocates a structural shift in poetry education and has explicitly positioned itself in opposition to the formats and → methods currently used to teach → poetry in schools, which consist largely of → reciting memorized poems and their substantive and formal analysis. In this sense, “Le Printemps des Poètes” can be associated with the → reformative function of cultural mediation for the school system. However, it fails to address the possibility of integrating feedback from the schools into cultural mediation. It calls for greater attention to active experimentation and project work for students as alternatives to the → teaching of art history facts practiced by the majority.13 The turn toward practical activities in educational structures is being widely promoted, in accordance with the latest theories about learning. It promises a greater degree of learner involvement, a free development on their part and thus improved learning achievement. However, it also results in the neglect of the diversity of pupils’ backgrounds, thereby reinforcing existing inequalities. The contradictions which arise from this situation are discussed in detail in → Text 4.RL. “Le Printemps des Poètes” does not act directly by, for instance, setting up partnerships between artists or creative practitioners and schools, instead it functions as a sort of intermediary between the various individuals and organizations and provides a platform for networking, by providing information, contact details and possibilities for advanced training. The association has also developed an incentive system intended to encourage people and institutions in this cultural field to engage in their own poetry mediation and dissemination activities. To do so, “Le Printemps des Poètes” focuses on the creation of structures and long-term implementation of literary activities in the school routine. It does not offer specific programmes to schools (such as those associated with the Morley Festival), instead, it uses the label → École en Poésie to reward schools for their commitment to poetry. The label is produced in collaboration with France’s Office Central de Coopération Scholaire [→ OCCE, Central Office of School cooperation]. Schools have to carry out at least five to fifteen activities falling under two sets of criteria in order to qualify for the label “École en Poèsie”. Proposed activities, such as taking part in poet festivals or initiating an exchange of letters with a poet, fall under the set of criteria called “poetry at the focus of the class”, as does the showcasing of non-French language poetry from other countries and its translation. The other set of criteria relate to enhancing the visibility of poetry in schools, by, for example, naming classrooms after poets or publishing an article about poetry in the school newspaper. In return for their participation, schools receive special support for the activities, in the form of advisory services, professional training for the teachers involved and communications support using the websites of “Le Printemps des Poètes” and the OCCE. In an analogous programme, whole cities or villages can acquire the Village/City-en-Poésie label. For that label too, there are a set of → fifteen criteria, a certain number of which must be met (three to five, depending on population size). In 2012, 22 communities, thirteen villages and nine cities, were awarded with the label. The honour can be used in a city’s marketing, an area in which the → cultural factor plays an increasingly important role. Culture as a “soft” factor contributing to the attractiveness of a given location has long been of economic relevance, as a draw for both tourism and, indirectly, for businesses.14 The label promises the cities and communities certain advantages relating to communication of their festival activities in March and thus greater visibility as a culturally active region. In addition, this sort of distinction tends to have a positive impact on subsidy acquisition. The Morley Literature Festival also addresses schools with its activities. For instance, in 2009, the programme → Find Your Talent supported partnerships between festival authors and all of the Morley schools as an added level of the festival. “Find Your Talent” was a supra-regional programme in England funded by the Arts Council with the mission of increasing schoolchildren’s involvement at the various levels of cultural production. The idea was that rather than addressing them as the recipients of cultural messages, the children should be equipped with knowledge allowing them to intervene in the → programming and production of cultural offerings. At the same time, the programme was supposed to ensure that students were exposed as regularly as possible to various forms of the arts through projects, workshops and other offerings, in order, as the programme’s name implies, to discover their own → talents. The view that talent itself is a construct based on bourgeois values was not addressed. The English programme subsidized the partnerships between local schools and the festival authors for the Morley Literature Festival. Fifteen local schools worked with authors in a partnership structured as → action research. The objective was to develop ways to better integrate literature in the schools. The approach was similar to that of “Le Printemps des Poètes”, in that an attempt was made to integrate poetry in a subject like mathematics, for example. The results of the partnerships are not documented on the Internet site, but according to Jenny Harris, the projects led to the creation of long-term, personal contact with the local schools.15 In another project carried out in the “Find Your Talent” context, young people created their own literature events with the assistance of a youth librarian. In collaboration with “Reader Development”, → literature days in libraries were developed to increase the attraction of libraries for young people in Leeds, and particularly in Morley, in an endeavour to promote reading. In both cases, school children were integrated as partners in the further development of literature mediation. Their knowledge was recognized as relevant for improving literature mediation, which suggests that a → co-constructivist understanding of teaching and learning was in play and that the project was intended to serve a → transformative function with respect to the programmes offered by the institutions involved. However, the results of the partnerships cannot be assessed, due to the absence of relevant documentation (see Omissions). In 2012, the festival’s offerings for schools can be associated more with a → reproductive discourse: large-scale events featuring authors were initiated at several locations in Morley, including a reading at the town hall attended by more than 500 students16 and there was a possibility to schedule authors to come to workshops held in schools. This change is primarily the result of a package of spending cuts in the cultural arena introduced after the change of government in 2010, which caused the “Find Your Talent” programme to shut down. In summary, these examples of partnerships with schools reveal a fundamental difference in the approaches used by the two festivals. While the Morley festival influences the content of the various initiatives, “Le Printemps des Poètes” does not take responsibility for the implementation or quality of the individual activities, only putting forth a platform for stimuli and suggestions as to content. The programme of “Le Printemps des Poètes” is a reaction to the fact that only one percent of the French population reads poetry regularly17. Reacting to that figure, it concentrates on building networks, communications campaigns and the initiation of training and continuing training offerings for interested professionals (teachers, librarians and organizers, and also amateur poets), unlike the Morley festival, which maintains a strong local focus in its activities.How is Cultural Mediation Carried Out?

What formats and methods are used in the festival’s mediation activities?What is Transmitted? “Le Printemps des Poètes” identifies one main theme each year, which connects the various activities. In past years, the spectrum of themes has included unrestricted, open themes, such as “poetry and song” in 2001 or 2004’s “hope”. Since 2007, the themes have been associated with specific poets, such as “love poems” under the title “Lettera Amorosa, le Poème d’Amour” in homage to the poet René Char.18 Works relating to the theme are also commissioned from poets in this context. Thus “Le Printemps des Poètes” pursues a two-pronged strategy: the organization hopes to buttress the conditions of production of contemporary authors and, at the same time, improve the level of → reception of poetry, by → changing the image of poetry and positioning and revitalizing it as an artistically independent, contemporary genre. In both approaches, one can detect a definite hierarchization of arts mediation relative to arts production. The resulting fields of tension are discussed in detail in → Text 1.RL. The multidisciplinary approaches adopted in “Le Printemps des Poètes” provide a concrete example. In 2011, a short film festival, “Courts Métrages Ciné Poème”, was started in partnership with the City of Bezons. According to its director, Jean Pierre Siméon, the festival was designed to attract a larger public by offering a combination of film and poetry.19

Poster for the short film

festival Cine Poème 2013

© Printemps des Poètes

By failing to mention the project, “Le Printemps des Poètes” reveals that it attaches only secondary → importance to it. The same attitude manifests itself in the link with music, which the organizers also see as a way of reaching additional audience circles. The focus there lies on production again however, with a → competition for poems put to song and a → composition competition. Mediation is not mentioned in the festival’s own presentation of itself and its mission, “to inform, to advise, to train, to accompany projects and support the work of contemporary authors, publishers and artists”20.

By concentrating its activities on the dissemination of literature in various contexts, the festival is applying an → understanding of cultural mediation which implies that even the mere exposure to art involves an educational dimension. The key premise of the programme is thus based on the idea that knowledge of and coming into contact with poetry will inevitably lead to a better reception of this genre. As a consequence, the festival’s activities aim specifically at → enlarging the readership for poetry, without questioning the practices or the form of contemporary poetry. The low readership is understood to be resulting from ignorance on the part of potential readers, or their educators, a deficit which “Le Printemps des Poètes” seeks to remedy through appropriate actions (professional training and an incentive system). No attempt is made to make use of the opportunity to put poetry and its social marginalization at the focus of mediation activities and, for example, explore why so few people read this literary genre.What is transmitted and for whom?

On what mediation subject matter does the festival concentrate and at whom are its activities addressed? The Morley Literature Festival focuses its festival programme on the integration of successful authors, such as Barbara Taylor Bradford or the science-fiction writer Ian Banks21, and points to those authors in its presentation of itself. This means that the programme takes an→ affirmative approach with respect to the book market and is oriented to some degree toward → marketing. This is explained, according to the festival director, by the fact that the well-known authors can be engaged as part of their book tours and thus relieve the festival budget of the need to pay their full expenses. The presence of best-selling authors makes it possible for the young and less well known authors to be invited to the festival as well. According to Harris, this approach is primarily a result of the festival’s financial circumstances. With a budget of around GBP 30,000, it is a small-scale festival, which has to rely to a great extent on → volunteer work. Budgetary constraints have a big influence on programming options. Given its comparatively low status and a less-than-prominent venue (Morley), the festival justifies itself to a large extent in terms of visitor numbers. The aim, according to Harris, is to offer a qualitatively sophisticated cultural programme to the local population of Morley through the festival. The local population is composed predominantly of → white working-class people and the town has had to struggle with image problems on more than one occasion in the past. Currently, the situation is changing due to an inflow of ethnic minorities, artists and students. According to Harris, one central concern of the festival is to engage with the population to reflect on the town’s historical development, taking the current changes into account.22 However, a survey of the subjects addressed in the festival’s activities and the cultural mediation offerings of Morley, ranging from readings to creative writing workshops to artist interventions in public space, yields little information about the criteria providing the basis for their selection.

Screenshot of the Morley festival’s website, November 2012 The festival’s → spectrum of activities ranges from tours of the town, to a literary lunch with Tim Ewart, royal correspondent for a national television broadcaster, through to an evening of folksongs. No thematic linkages among the activities could be detected in the readings or selection of authors. However, the workshops and projects do reflect a concentration on the town of Morley, as the comments of the festival’s director above suggested. In addition, the festival seems to be taking a “something for everyone” approach, though the programming is oriented towards the presumed interests of defined target groups. The layout of the festival’s programme is another indication of this: it is arranged by event format “author talks, workshop or discussion”, the group being addressed “children and families” and the section “music, art, sports”. This makes it possible to orient quickly within the programme according to one’s interests and reflects a clear targeting according to → conventional definitions of target groups.

Who “does” Cultural Mediation?

Who carries out mediation activities? With whom does the work within the project get done? How is cultural mediation carried out? Drawing on specific project examples from the festivals, approaches and methods used in the mediation activities are discussed. What does cultural mediation do? What mediation discourses can these activities be associated with?In 2012, the artist interventions of the Morley festival were supported by “Leeds inspired” (see above). In a → public call for submissions, the festival announced that it sought to commission work which “playfully responds to the festival’s theme of ‘Fact / Fiction’...” and invited artists to come up with “cross-art projects with the aim of engaging local audiences in imaginative and unexpected ways”. Four small commissions were offered to Leeds-based visual artists to create works addressing the fact/fiction theme in the context of “Feral-Nowledge” a text-based work commissioned from the audiovisual artist → Paul Rooney which would “blur factual and fictional moments from Morley history”. The artists’ projects were to take the form of street signs to be put up in Morley’s pedestrian zone. The public would be encouraged to discover and map the signs for themselves. Commissioning fees of GBP 200 were offered, with an additional GBP 200 available per commission as a materials budget. Even given the narrowly defined framework and concept that the artists would have to adhere to, the budget for project creation and realization seems inadequate. According to the Arts Council in England, → compensation for artists and cultural workers should be paid at a daily minimum of GBP 175. GBP 200 for idea and realization is likely to work out to far less than that daily rate. The commission announcement suggests that by involving visual artists in a literature festival, the festival’s organizers saw an opportunity to set the stage for the “imaginative and unexpected”23. However, they provided neither the appropriate level of funding nor scope for artistic creation. Nonetheless, five local artists24 did apply for and receive commissions, and developed alternative public signs which were posted in the town centre in a project titled → Signs of the Times. Given the deterioration of the conditions under which artists work in England, this type of strategy seems to be relying on intangible benefits associated with participation in the festival as a substitution for monetary compensation. This is in line with the way that → volunteer work is exploited in the cultural sector and the → economics associated with that.

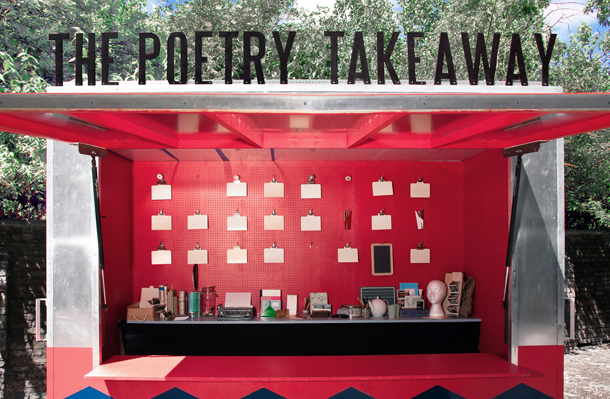

© Poetry Takeaway The festival also integrates freelance mediation projects into its programme. In 2011, for example, → The Poetry Takeaway project was part of the programme. The Poetry Takeaway transposes the concept of a street-food truck to the domain of literature. A trailer is set up on a public square or festival venue; in that and in other ways the project takes its aesthetic model from the typical burger van. The group of authors offer passersby the chance to order a made-to-order poem. This implicitly frames the project as being in opposition to the widespread notion of poetry writing as a contemplative activity which takes place largely behind closed doors. Instead, the creative act is accelerated by a self-imposed deadline, requiring the poem to be supplied within less than ten minutes. “The Poetry Takeaway” also uses the language of its catering model to describe itself, referring to the authors as “poetry chefs” who “cook up” the poems and deliver them to their customers packed in a box or wrapped like a burger. By taking this approach, the group is also playing with the increasing service-provision orientation in the art world. By transposing the act of “ordering, producing and delivering art” into a performance, they are criticizing the prevalent conditions of production and, at the same time, applying them in a caricatured, but positive form, to their own activities: → How it works:

1. Queue up to speak to one of our fully trained Poetry Chefs.

2. You’ll be allocated to a Poetry Chef, who’ll discuss your order with you in order to ascertain its style and content etc. No knowledge of poetry is required – a few details about you, what you’re up to, what you like and what you’re into, will suffice. Alternatively, if you want a poem similar in style to your favourite by [insert not too obscure poet], our dedicated Poetry Chefs can successfully operate from your instruction.

3. Your Poetry Chef will retire to the kitchen to cook up your bespoke order, leaving you free to soak up the atmosphere.

4. Within ten minutes or less, you’ll be greeted by your Poetry Chef who’ll perform your poem to you. And hand you a written copy, either open or wrapped in our beautifully-designed takeaway boxes.» The project’s → deconstructive function is also evident in the wording used to describe the author’s activities, which takes them completely out of the literary context. By placing them in a new context, this approach puts the spotlight on the mechanisms of art production. The result is that writing poetry is presented more as a craft, deglamorizing the author myth to a certain degree.

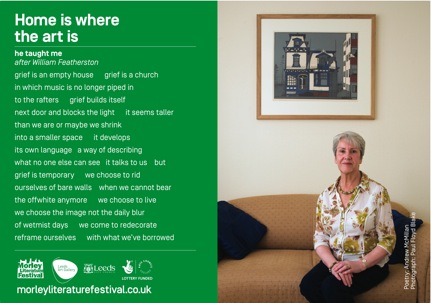

Poèmaton, © Isabelle Paquet “Le Printemps des Poètes” also integrates the educational activities of freelance groups in its programme. Certain projects, poetry exhibitions, festival groups and individuals from the poetry scene, which satisfy the association’s quality standards, are presented and linked in a network under the label → Sélection Printemps des Poètes One project presented in this selection has similarities with “The Poetry Takeaway”. → Poèmaton uses converted photo booths inviting passersby to take a seat and listen to a poem. Rather than receiving their photographs at the end, participants receive a printout of the poem and information about its author. Unlike “Poetry Takeaway”, which permits direct contact with the authors and involves the deconstruction of poetry and the associations people have with it, Poématon creates a venue for the reception of poems in unexpected places. Its → mediation goals remain within the realm of communicating the work. Hence “Poématon”, again unlike “Poetry Takeaway”, aligns itself with the → reproductive discourse. In addition to the activities on the festival programme, the Morley Literature Festival establishes long-term partnerships. One example is the 2011 project “Home is where the art is”, which ran in collaboration with the “Picture Lending Scheme” of the Leeds Art Gallery. The → Picture Lending Scheme is a kind of library for art, started in 1961, with the aim of enabling Leeds residents to enjoy original works of art in their own private flats or houses. The → festival’s blog was used to locate six households in Morley willing to borrow works from Leeds Art Gallery for the project. Participants had to consent to have photographer Paul Floyd Blake take their picture with the work they chose to borrow and to discuss the reasons for their choice with poet Andrew MacMillan, who used that exchange as the foundation for a poem. The photographs and poems were exhibited in the Leeds Art Gallery during the festival. In thanks for their participation, the borrowers were invited to what the festival blog called a “VIP opening” of the exhibition. Thus, the call to the participants took advantage of the mechanisms of exclusion operating in the artistic field as an incentive system, granting participants privileged access for a limited period of time. One has to assume that the residents who applied to participate in the project were able to recognize and exploit the → symbolic capital associated with it. In this sense the project is in implicit opposition to the intentions behind the “Lending Picture Scheme”, i.e. to promote engagement with art among as heterogenic a public as possible. The mechanisms were also reinforced by the opportunity offered to participants to invite a curator from the Leeds Art Gallery into the home to discuss the borrowed work, under the slogan “Tea with the Curator”. This arrangement held the potential for an exploration of questions about the institution and its collecting strategy and the representation of art in private spaces. As it was implemented however, the project focused on brief encounters between artists, curators and audience. The exchange was limited to a single photo-shoot and the narration of a story that became the starting point for a poem. Artistic engagement rested with the artists alone – nor did exchange about → artistic processes take place. The residents were involved but they remained in their role as the perceivers of art and thus represented consumers of culture for the festival. In approaching participants who were already interested and in confirming the dominant logics of the system, the project failed to exploit its deconstructive potential and thus remained embedded in the → affirmative discourse. No engagement with questions relating to → mechanisms of representation of individuals and organizations in the fields of photography or the literary arts occurred.

Screenshot from “Home is where the Art is”; poem: Andrew McMillan, photo: Paul Floyd Blake Formally, the photographs created in the project evoke depictions of collectors before their works. They also confirm the assumption that the homes involved were primarily those of well-situated members of the → majority society. The → project’s outputs – photographs and poems – are documented online, but can only be found via the → festival’s blog site. Another project initiated in 2011 is → Now then!, a blog intended to present the past and present of Morley through text, sound and imagery with inputs from Morley residents. The project was led by the scriptwriter and playwright Emma Adams, who invited Morley residents to document the town by sending in their own stories, or their own texts and images. The project encompassed writing workshops and other events held during the festival, though it continues to operate today as a blog or a growing archive in which anyone who is interested can participate. The project’s description suggests that it involved partnerships with various communities in Morley, in which the object was to rewrite the history of Morley based on the personal experiences, biographies and memoirs of Morley residents. However, the website documents only one public event in Morley’s indoor market where the artist gathered the stories of passersby which she then put into writing for the blog. The opportunity to focus on the historiography of Morley and work with various population groups to rewrite it was not taken up. Instead, another focus was directed toward “People in Action” a social group for people with cognitive impairments, which meets on a weekly basis in a community centre for various activities, such as knitting, bingo, making music. Impressions from one visit to the group were documented in a short → video that says very little about the project and offers minimal insight into its process because it fails to describe either the project or its own role within it. The people appearing in the video are asked about their activities in the group and in Morley more generally. This approach raises questions relating to the selection and the weight given to this group. All the more so because “People in Action” represents a community which is marginalized and thus of great symbolic significance for the artistic field, whose participation in an institution’s programme, in this case the Morley Literature Festival, is advantageous for the → legitimization strategy of the institution. In this case the problematic dimension is exacerbated by the fact that it is the only video produced in the “Now then!” project aside from a short → video showing the artist at the market. Harris puts these → omissions down to lack of experience with the approach. The conditions and resources to support a qualitative use of a participatively structured project were not in place. Accordingly, from the perspective of the festival’s organizers, the project was unable to meet their expectations, e.g. deliver a text authored collectively by the residents and the authors. In this case, it is clear that a reflexive form of documentation would have been more appropriate for the way project turned out, as this would have required the failure to be described and the experimental nature of the project to be presented more clearly. As it is, the presentation of the project casts the initiators in a misleading light, suggesting a low degree of reflexivity and a failure to appreciate the potential for learning offered by failed projects. In this instance, it would have been wiser to → dispense with the presentation of the project completely, which would have protected the people involved from being put out on display.

Omissions

Reflexivity with respect to one’s own work: though both projects have run for many years, neither provides an assessment of changes over that time. Statements about objectives which have been achieved, modifications to procedures over the years, adjustments to implementation or possible missteps would make it possible to trace the development of the festivals and make specific statements about real projects. Documentation of individual projects: in the case of both festivals, there are incongruities between the aims of the festivals’ initiators as communicated and the documentation of activities that have already taken place, which does not offer much detail. As a result, very few conclusions can be drawn about past project plans and implementation. Therefore the qualitative assessment of the project must concentrate on the conceptual approach and the expectations of the initiators. Whether and how the planned approach was applied or is being applied, remains unclear. Teaching and learning concepts, level of participation: the largest lacuna resulting from inadequate documentation of past activities relates to the learning and teaching concepts applied and the level of participation of participants. Information on those aspects can only be drawn from rather cryptic descriptions of projects and their aims. This analysis can address only the conditions and aims for a planned project, in those cases where they were indeed presented.Conclusions

Although certain aspects of the festivals have been quite thoroughly documented, the largest gap in the analysis is in the area of a qualitative evaluation of the mediation projects. As → Text 8.RL makes clear, such an evaluation can only be performed if a project’s structure, processes and results can be analysed in the light of a project’s objectives. That requires transparency with respect to the initiators’ objectives, what actually occurred during the project and its results, or the initiators themselves must place the project’s history in relation to the formulated expectations. In cultural mediation, it is rare to find → project descriptions and documentation that actually do this. This is in part due to the budgetary constraints associated with cultural mediation. Exacerbating that situation are the conflicts of interests fuelled by the differing aspirations for mediation. As a result, the primary purpose of documentation tends to be that of → legitimization of the project, which produces a tendency to tell success stories only. If others are to learn from project documentation, it would be important to render transparent and analyse failures, problematic aspects or complications. Doing so, however, often entails a risk of losing funding or putting oneself at odds with the sponsoring institution. Accordingly, in presenting their projects, cultural mediation/project initiators tend to follow the dominant → modes of representation found in cultural mediation, as the discussion of the two festivals has illustrated, and thus contribute to the maintenance of the status quo, though not always consciously.Materials

The following materials were available for the project analyses: Le Printemps des Poètes, France- presentation of the project on its → website

- dossiers relating to cultural mediation in the literary field

- other information about the festival found online

- presentation of the project on its → website

- video documentation on You Tube

- telephone interview with the festival director Jenny Harris on 11 Dec. 2012

1 The description provided on the festival’s website reads: “Morley Literature Festival in Leeds is an annual week-long festival in October celebrating books, reading and writing” → http://www.morleyliteraturefestival.co.uk/about [17.11.2012].

2 See bibliography on Jean-Pierre Siméon: → http://www.printempsdespoetes.com/index.php?url=poetheque/poetes_fiche.php&cle=3 [18.11.2012].

3 A detailed paper on France’s current school reform is available on the website of the country’s education ministry: → http://www.refondonslecole.gouv.fr/la-demarche/rapport-de-la-concertation [10.11.2012].

4 In the original French: “une éducation culturelle, artistique et scientifique pour tous”.

5 Refondons l’école de la République, Rapport de la concertation, p. 40; see Resource Pool MCS0108.pdf.

6 Cf. op. cit.

7See France’s cultural policy concept of the 2012 – 2014 legislative period,

→ http://www.culturecommunication.gouv.fr/Politiques-ministerielles/Developpement-culturel/Education-populaire/Conventions-pluriannuelles-d-objectifs-2012-2014 [10.11.2012].

8 See the website of the association Verein Public Private Partnerships in Switzerland → http://www.ppp-schweiz.ch/de [10.11.2012].

9 See Sack 2003.

10 Phinn 1999; Phinn 2001.

11 Phinn 2000.

12 Walter Siebel and Harmut Häußermann coined the term festivalization (Festivalisierung) in 1993 in their article “Festivalisierung der Stadtpolitik”. The term refers to the concentration of time, space and financial resources on a single event or project. See Häußermann, Siebel 1993.

13 See Refondons l’école de la République, Rapport de la concertation, p. 40; see Resource Pool MCS0108.pdf.

14 See the April 2011 issue of KM Magazin, which focused on urban and regional marketing (KM 2011); for more on the significance of the creative industries in Switzerland, see also: Weckerle et al 2007; Summary data also published at → http://www.creativezurich.ch/kwg.php [15.11.2012].

15 These statements are based on a telephone conversation between the author and Jenny Harris, the festival director [11.12.2012].

16 Statements by Jenny Harris [11.12.2012].

17 → http://www.printempsdespoetes.com/index.php?rub=2&ssrub=16&page=59 [15.11.2012].

18 All Le Printemps des Poètes themes are listed at → http://www.printempsdespoetes.com/index.php?rub=4&ssrub=23&page=13 [18.11.2012].

19 → http://www.printempsdespoetes.com/index.php?rub=3&ssrub=21&page=75 [17.11.2012].

20 → http://www.printempsdespoetes.com/index.php?rub=4&ssrub=23&page=13 [17.11.2012].

21 → http://www.barbarataylorbradford.co.uk [10.11.2012] and → http://www.iain-banks.net [10.11.2012].

22 All statements cited here were made by Jenny Harris in the telephone conversation with the author on 11 Dec. 2012.

23 → http://www.a-n.co.uk/publications/article/193995 [10.11.2012].

24 Artists who participated in “Signs of the Times”: Paul Ashton, Amelia Crouch, Clare Charnley, Jess Mitchell and Vikkie Mulford.