CS.1 “Schulhausroman” and “Auf dem Sprung”

Introduction

This case study looks at two cultural mediation projects in the literature domain. Both projects are set in the context of schools and they are also similar with respect to the people they target and their participative orientation. Although the nine key questions discussed in the main part of this publication provide the matrix for the analysis, they have not determined the order in which topics are addressed in the discussion. The order rather focuses on the aspects that the authors view as being of central importance for the analysis of the project. In the case of both “Schulhausroman” [Classroom Novel] and “Auf dem Sprung” [On the Go], the analysis concentrates primarily on the targeting and participation of the young people and on the specific structure of the collective activities, and unlike → Case Study 2, less on the structure of the projects and the strategic approach of the initiators. The questions discussed cannot always be clearly separated, as they have a tendency both to overlap and to raise other questions.Schulhausroman

Cover

© Provinz GmbH

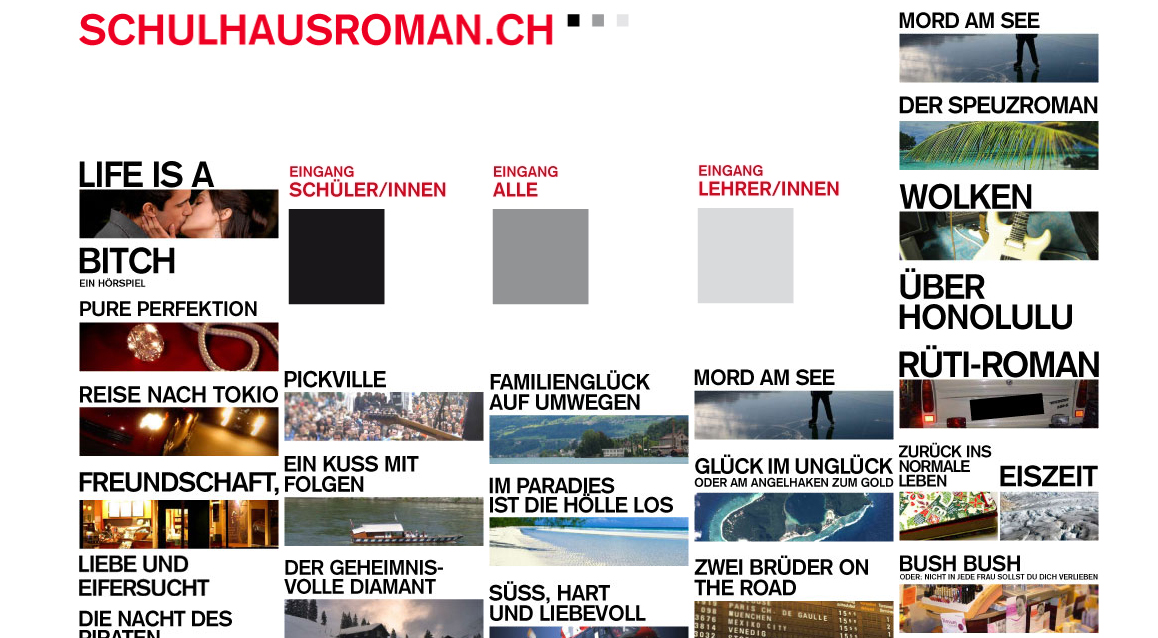

Auf dem Sprung

Exhibition poster

© Archiv der Jugendkulturen

Discussion

Cultural mediation: Why? Motivations and objectives of the project initiators. How does cultural mediation work? Function of the project for the institution, with special focus on audience development. Author Richard Reich developed the project → Schulhausroman in response to the reactions of pupils to his readings. He wanted to engage children thought to be poor learners with literature through active involvement and practical experience and felt that the reading format was inadequate for that. Thus the project’s initial intention with respect to literature falls within the scope of audience development and can be associated with the → reproductive discourse. In the open structure of collaboration in the project and in the participants’ engagement with the authors in the collective production of a work with mutual exchange of knowledge, the project also contains→ deconstructive elements. This applies both with respect to the reception of authors and for the field of literature itself. Rather than perceiving the speech of the young people as defective, the authors understood it as representing specific knowledge to be integrated within the writing process. The project developed a deconstructive function with respect to literary circles. In taking the name “classroom novel”, by aspiring to collaboration between them and famous authors and by holding the readings in prestigious cultural institutions or cultural centres focusing on literature, the project was addressing the pupils not as a future audience for literature centres or readers. Instead, they were deliberately given the status of partners, in order to take the → young people as young authors seriously and generate visibility for their themes and their language. By doing so the project actively set itself against existing exclusions, turned the purported linguistic disadvantage of the young people into a new literary asset and, at the same time, invited discussion of the → current positions of artists (or authors). Since it is based in schools, the project reaches young people who do not fall within the spectrum of the educated bourgeoisie. It differs from conventional, → formal learning situations in lower secondary education 2, in that- no grades are assigned;

- it focuses on → collective production processes rather than individual performance;

- it uses an experimental and open-ended approach;

- it has authors act as mentors (coaches);

- decisions determining the project’s evolution are made collectively;

- experiences of achievements constitute a substantial part of the project for everyone;

- characteristics defined in the school context as weaknesses are redefined as strengths, “wrong” becomes “right” or “exceptional”;

- and finally, the possibility of failure is presented as lying not with individual pupils but rather with the professionals (the authors).

Cultural Mediation for Whom?

How and in what role are people invited to take part, what benefits does the project explicitly promise to participants? What are the motivations, needs, deficits of the participants and how are participants implicitly expected to benefit? Both projects entail working with pupils who are considered to be disadvantaged with respect to their situation within society. By targeting adolescents in non-university track secondary education, the “Schulhausroman” project acknowledges the inequality of opportunities which is both prevalent within the school system and induced by it. In the project, the form of school in the lower level of secondary education rather than ethnic or national origin was the key criteria for disadvantaged status. This reflects the correlations between of the use of culture and educational background.4 The structure of the collaboration makes it clear that everyone, students and authors, is considered to be taking part in a → process of learning and development. This means that differences are viewed as specific forms of knowledge are acknowledged within the project, which uses the energy engendered through the → engagement with literature against the backdrop of those differences to fuel the → educational process. At first glance, the project might be seen as pursuing an egalitarian agenda by making participation compulsory for all students in the class, regardless of their grades or motivation. However, compulsory participation means that students did not choose of their own free will to work in the project, a circumstance which reproduces the → hierarchy of learners and teachers which has long characterized formal educational structures. This is reinforced by the presumption that engagement with literature is fundamentally desirable and useful. A reflective approach to this situation would not gloss over of the tensions inherent in combining the desire to have young people participate in the writing process and taking their abilities seriously with the structural conditions required to achieve those aims. Instead, a reflective approach would attempt to render those tensions productive, by setting up an open process which encompasses the possibility of failure. Aware that a large portion of society tends to ignore literature – and contemporary Swiss literature in particular, the project creates an opportunity to examine the significance of the work of authors in direct exchange with a non-reading audience. Thus the role of authors is actively scrutinized. In addition to encouraging adolescents to engage with literature, the project has the objective of initiating a learning process in the writers, specifically, creating in them an awareness of their own privileged stance and recognition of the fact that there are population groups for whom Swiss literature has no relevance due to complex cause and effect relationships. The thematic focus of “Auf dem Sprung” means that its target participants are young people with immigrant backgrounds. In this regard, the project draws on a → concept of culture which assumes that an individual’s attitudes and perspectives are primarily determined by ethnic origin, religion and language. In this view, culture is treated as a dominant constant which encompasses no other categories, such as education, social status, physical dispositions, gender or sexual orientation. Thus in this type of concept of culture such categories are not considered to be factors which limit and interact with one another. A reductive concept of culture of this kind is inevitably associated with hierarchization: although the project explicitly opposes discrimination based on ethnicity and operates in an “embracing diversity” context, even in doing so it implicitly reproduces essentializations and stigmatizations. The majority ethnicity, and thus its presumed culture, remain the standard: diversity is framed as deviation from that standard. Thus the young people in the project represent themselves, but also, inevitably due to the use of this reductive concept, they also represent their age group and their ethnic affiliation or → national origin. In many instances the texts and images produced by the young people rebel against this thematic constraint. They do not limit themselves to the effects or influences associated with their national, linguistic or religious origin. They address a broader range of content: ranging from encounters with neo-Nazi violence, to hugely varied experiences of discrimination and belonging, phobias and hobbies, right through to the ability to travel almost all the way around the world by virtue of having relatives ready to receive them almost everywhere. The variety of texts and contents produced by the adolescents clearly demonstrate that ethnic origins and the religious affiliations and languages associated with them represent only three among many influential factors. It emerges clearly that considering these categories in isolation tends to produce a fragmented picture which in no way reflects the complexity of individuals and social contexts.

Photo: Sarah Charif

© Archiv der Jugendkulturen

Sarah Charif, Photo: Jörg Metzner

© Archiv der Jugendkulturen

“Well, unfortunately we do not have that many family members in Berlin. There are about 150 to 200 people, and they do not even all live close together. There are a few living in Spandau, Wedding, Neukölln, Kreuzberg, Schöneberg and in Tempelhof. We are a huge family. That would only be the ones who live in Berlin.”

(Sarah Charif)

Photo: Birkan Düz

© Archiv der Jugendkulturen

Birkan Düz, Photo: Jörg Metzner

© Archiv der Jugendkulturen

“I am in Berlin and I’m 16 years old.

Sometimes I am German.

Sometimes I am Turkish.

Sometimes I am Kurdish.

Sometimes I am Alevi.

Sometimes I am Zaza.

When I am in Turkey, I tell the people there that I am German,

When I am in Germany, people tell me that I am Turkish.

Or I say that I am Turkish. […]

If I am alone, I feel like I am Birkan.

If I am with Germans, Turks, Kurds, Alevi, Zazas, I feel like myself.

I am Birkan.”

(Birkan Düz)

However, the project presentation created by the project organizers does not reflect the → diversity of categories used by the young people to identify their position in the world (as opposed to an imaginary, essentializing diversity of cultures). This suggests a failure on their part to exploit the potential to shift institutional misconceptions by engaging with the texts and photographs. This is one indication of how extremely difficult it is to eliminate → culturalizing attributions.

Another dimension of the way the project targets the adolescents is associated with the fact that the teachers were responsible for selecting the project participants. The project documentation does not reveal the criteria used for this selection. The act of selecting is of crucial importance, however, particularly with respect to the function of the project for the pupils. Selection might be used to reward some students and entail yet another exclusion for the others, exacerbating the inequalities within the school; but it might also employ the reverse logic: being considered more “difficult” could qualify someone for selection for the project (see Omissions, below).

The aims of having students experience a sense of achievement and offering them a public platform are two things the two projects have in common. Through the high level of involvement by the adolescents in decision-making with respect to aesthetics and content and through the partnership structure created for the practical activities, both projects succeed at → enabling young people to identify with them, perceptible at least at the level of representation. In both projects, the young people are defined as authors and they have the opportunity to present themselves confidently as such. However, interestingly, in the “Schulhausroman” project, which is aimed at high culture, this occurs in a considerably more egalitarian and thus more radical manner than in the “Auf dem Sprung” project, which is positioned in a socio-cultural context, where participants have undergone a selection process.

Sometimes I am German.

Sometimes I am Turkish.

Sometimes I am Kurdish.

Sometimes I am Alevi.

Sometimes I am Zaza.

When I am in Turkey, I tell the people there that I am German,

When I am in Germany, people tell me that I am Turkish.

Or I say that I am Turkish. […]

If I am alone, I feel like I am Birkan.

If I am with Germans, Turks, Kurds, Alevi, Zazas, I feel like myself.

I am Birkan.”

(Birkan Düz)

Who “does” Cultural Mediation?

→ Focus on cultural mediators: artists / mediators – their roles, intentions, aspirations and expertise. Only professional → authors are recruited to work with students in “Schulhausroman”. They serve as mentors and experts in their genre, literature. The selection of authors who are successful in the book market confers extra credence and significance to this role (though the participants do call this into question). The authors have a decisive influence on the course of the project, its linguistic and artistic evolution as well as the reception of its results in the literary field.5 The project initiators themselves attribute a key role in the project to the authors and refer to them in defining one of the essential aspects in which the project diverges from the formal teaching and learning situation in schools, which they associated with the possibility of failure: “The writing coaches (these are the authors), who encounter the non-homogenous class, are neither teachers nor social scientists working according to predetermined qualitative requirements. As a result, they develop a highly individual approach and in no sense do they create a neutral laboratory situation which one could duplicate in one class after another under comparable conditions. Thus, every schoolhouse novel is an experiment in itself, with an uncertain outcome – and the possibility of failure.”6 In the “Auf dem Sprung” project, the role of the authors is less tied to their market position. Moreover, they are not acting primarily as representatives of their profession. The two authors and the photographer have all published in their fields, but they have also been working for years as mediators in projects at the interface of art and society – largely in independent institutions associated with the → socio-cultural field. Thus they do not represent the occupation of artist or the art market per se, but are acting within the project largely in the capacity of mediators possessing artistic expertise. This positioning makes it clear that the primary objective of “Auf dem Sprung” is not so much the engagement with contemporary literature or photography, as with writing and photography as → tools to be used for (self-)exploration and (self-)representation by young people.Who “does” Cultural Mediation?

→ Focus on funding: what impacts do the amount, source and allocation of funding have on the project? The “Schulhausroman” project is carried out by → Provinz GmbH, a small business run by the initiators Richard Reich and Gerda Wurzenberger with a focus on writing and publishing. In Switzerland, the project is funded by multiple partners: the literature centre Literaturhaus Museumsgesellschaft, the City of Zurich’s Office of Schools and the foundations → Ernst Göhner Stiftung and → Mercator Schweiz.7 Since 2010 Pro Helvetia has also been funding the continuation of the project in schools in French-speaking parts of Switzerland. To some extent, the motivations of the funding bodies can be inferred from the presentations of the projects on their respective websites. While the project initiators demonstrate a very reflective approach in their phrasing, speaking, for instance, of pupils with “so-called” learning difficulties, the project descriptions provided by funding sources are not always as careful to differentiate. The foundation Stiftung Mercator, for example, describes the project on its website as follows: “Young people from environments providing little exposure to education write stories. Linguistically limited students with learning difficulties write novels […] The young people experience a sense of achievement. Their self-confidence is reinforced as well as their ability to express themselves verbally.”8 This description, focusing as it does on presumed deficits, nullifies the real potentials of the schoolhouse novel project, which lie in its potential to displace these sorts of dominant categorizations. Clearly, the degree of reflection applied to attributions can vary considerably within one and the same project. This is another instance that demonstrates how difficult it is to displace the dominant narratives which frequently reproduce exclusions and stigmatizations at the very places that projects like this one hope to combat them. The same applies to the project’s German and Austrian versions as well. 9 This emerges particularly strikingly in the wording on the → Wuppertaler website: “Students should be between the ages of 12 and 16, i.e. at what is quite a difficult age. […] Surprising results have been achieved, above all in Hauptschulen [non-university track schools], and with so-called problem children.” “Auf dem Sprung” received funding from the German Ministry for Family Affairs, Senior Citizens, Women and Youth, the Berlin Senate’s Representative for Integration and the Federal Agency for Civic Education as part of a federal programme promoting the value of diversity [Vielfalt tut gut. Jugend für Vielfalt, Toleranz und Demokratie]10. The motivation of the funding sources is thus in line with the discourse on integration in Germany, which aims at intensifying immigrant’s involvement in social, cultural and political contexts. 11 In this context, → cultural mediation is framed as a practice which supports those efforts.What is Transmitted, How is it Transmitted?

At which levels of the project are participants involved and to what extent?

Exhibition preparations

© Archiv der Jugendkulturen In the “Schulhausroman” project, the young people work with authors to develop their own texts, which they then analyse collectively in the context of the classroom before working on them further. The format of collective writing is a basic element of the project, involving the combination of individually written passages or sections of texts to form a single work. Exchange takes place at various levels, both with the authors and among the students themselves, in collective discussions about their own texts. The roles of authors and pupils are structured hierarchically in the project, but they do appear to allow an exchange of knowledge in both directions. The → high degree of participation of the students in the creation of the texts causes their language, which is normally considered defective in the school context, to be seen as valuable and taken up into the process.12 The authors support the development of the novel, analysing, together with the class, the credibility of protagonists, situations and actions, as well as stylistic aspects. Decisions relating to plot development are made by the students collectively. Generally, it is the authors who combine the individual text passages into a single text, which is then discussed with the class. Everyone participating in the project has access to a website which serves as a forum for collective work on the text. The involvement of adolescents in the “Auf dem Sprung” project is also structured as → participative. The individual histories of the young people create the framework for their collective work. Literature and photography, the two media in use, serve as instruments to access and means to express the world in which the students live. Unlike in the schoolhouse novel project, the work in “Auf dem Sprung” was undertaken by individuals, not collectively. The artists were on hand to assist and guide the young people. Like the schoolhouse novel project, analysis during the project addressed the linguistic development and → literary quality of the texts In the photography work the adolescents learned how to use the camera and the basics of image composition. The material available does not permit an assessment of the extent to which → critical analysis of the use of specific image materials and their implications took place.

Good Cultural Mediation?

Reflexivity, for instance with respect to- attributions vis-à-vis the target audience

- the contexts and discussions in which the project intervenes

- the development of empowering knowledge about the arts

- the privileged position of cultural institutions and those acting in them

- form and choice of representation (depiction of project outcomes, documentation, way participants are treated)

- how were the outcomes of the project created?

- who produced what at what level?

- what aesthetic language do the projects use?

- how do the results of the project stand up with respect to formulated objectives?

Documentation

Who publishes what about the project, where and in what way?

Screenshot of the “Schulhaus-roman” website, November 2012 One area that the reflexivity of the “Schulhausroman” project makes itself visible is the level of self-presentation. A → coherent design in all media, the selection of reading venues, the online presentation, the accompaniment and publishing of the texts online, wording, features and modes of access on the website and the publication of the booklets communicate a consistent level of professionalism running through all levels of the project. The website, with its three entries: “Student entry”, “Entry for all”, “Teacher entry” [square fields, left to right] makes it clear that different groups are being addressed and demonstrates a reflexivity about language by encompassing the linguistic variations associated with gender-inclusivity in German. This approach also provides a protected forum for exchange during the project period. In their minimalist design, the aesthetics of the website and the novel itself do not attempt to ingratiate by using forms associated with youth culture and convey a sense of seriousness. The students have some influence in the design, since they select a title image for their novel which is inserted into a frame provided for that purpose. The presentation of the “Auf dem Sprung” project took place primarily in the exhibition shown in the rooms of the Archive of Youth Culture from May to September 2009. The work of the young people and the young people themselves were presented in it using the following media:

- texts and photographs produced by the young people

- photographs of the young people taken by photographer Jörg Metzner

- documentary film about the project

- bound collection of texts (without photographs)

- fanzine13, which was created in a workshop

- poster and flyers

Reading held at Archiv der Jugendkulturen

© Archiv der Jugendkulturen The documentation itself does not specify the extent to which the adolescents were involved in the design of the exhibition or the selection or texts and images. An interview with the project initiators (project director and author), however, yielded information on this question that is discussed in the section on omissions, below. The form of communication and the formal structure of the outcomes correspond to preconceptions associated with aesthetics which are frequently associated with socially-oriented art projects. The lack of professionalism suggested by the use of communications media which do not reflect → the most recent design trends in the cultural sphere, suggest implications for the quality of the project as a whole – though this is not always justified. In addition to a lack of quality at the formal level, a lack of coherence in the overall way in which the young people are presented is another area for criticism. The film deserves praise, both for its content and quality, because it communicates respect for the young people and identifies all participating students by name. Strikingly, the bound collection of texts lists contains short biographies of only the professional authors and photographer are given in the appendix, the student participators go unmentioned. By not including the photographs, the text collection also fails to create a link between images and text and thus skips over one of the central aspects of the project. Aesthetically, the text collection evokes a work produced by a student at the end of a course, thus failing to produce a link between form and content. In a telephone interview with the project director, Klaus Komatz, this decision was justified by reference to the “private nature of the texts”.14 Unlike the fanzine and the film, the text collection published very intimate and private texts. According to Komatz, the desire to safeguard this intimate character was also the reason that in some cases the authors of certain photographs were not identified by name. This decision constitutes a breach with the treatment of the authors as a group. After all, the names of the young people are identified in conjunction with the texts themselves. The author Anja Tuckermann justified this omission by saying that the text collection was intended mainly for the young people themselves, and not so much for presentation to the outside world. The short biographies of the authors and photographer were intended, according to Tuckermann, to give the young people information about the people who ran the project, since the students had not asked about it during the project and thus were not aware of it. This justification raises questions about the exchange of information during the implementation process. The adolescents revealed highly personal aspects of their lives; the project leaders revealed nothing about themselves. To what extent can one speak of a participatory collaboration based on partnership when there was such a large discrepancy in the amounts of information available about the people involved?

“Auf dem Sprung” exhibition

© Archiv der Jugendkulturen The fanzine, created by the participants in another workshop led by a member of the Archive staff, contains the names of the students, texts and pictures. Thus on the whole the project displays considerably inconsistency with respect to identifying the adolescents; the differing approaches and the differing reasons supplied for them suggest a fairly non-reflective attitude toward issues of → representation. An evening discussion on the subject “Islamic and Islamist youth cultures”, an event held in parallel to the project, is also indicative in this respect. The event was documented as follows on the Archive’s Internet site: “Novel hybrid lifestyles which are based in various ways on Islam have emerged among Islamic youth in Germany. While some manifestations of these youth cultures tend toward the traditional/religious or typical adolescent/provocative, others take up Islamist attitudes and lifestyles and thus feature extremist elements. How can one see clearly amidst the multitude of attitudes, music, sermons, styles of dress and symbols? How is a centuries-old religion being repackaged to seem cool and appealing to the young? These questions were discussed in the context of the exhibition by a group of around 85 interested individuals. Citing numerous examples, the speakers Ibrahim Gülnar (→ Stiftung SPI Ostkreuz15) and Nadine Heymann presented and put forth for discussion the models of life and orientations of young Muslims in Germany.16 The young people themselves did not have a voice at this event for experts and thus were confined to the role of exhibition pieces, tolerated for a moment in a → hegemonic space for the purpose of the project’s presentation of itself, as long as this remained limited to self-presentation and so long as the rules imposed remained unchallenged. This shows once again that the project failed to recognize its own true potential with respect to participation, visibility and collective design or decision-making at different levels and was therefore unable to take advantage of it. In “Auf dem Sprung”, which was constituted primarily of the young people representing themselves, authors and work become quasi a single entity. The texts of the “Schulhaus roman” project do speak to the issues and worlds of the young people – but they do so through the protagonists portrayed in their works, as is generally the case with authors, rather than directly.

Local and Historical Context

For which discussions and local contexts is the project of relevance? What category of practice of cultural mediation does the project fall into? Because of its links with the Archive of Youth Cultures, the project “Auf dem Sprung” should be seen in the context of Soziokultur [socio-culture]. The Soziokultur context refers to a position on culture which developed in the 1970s to counter the marginalization of the arts and culture in society. Hermann Glaser17, who coined the term socio-culture, believed that all cultures should be “socio-cultural” in nature. Art should engage more closely with daily life and the issues in society and be less self-referential. Cultural policy conceived in this spirit would be seen as social policy. Although there is now a demand that socio-culture and so-called high culture come closer together, for the most part they still comprise two worlds which often remain completely separate from one another in terms of the individuals and institutions acting within them, though they can and do influence one another. With respect to hierarchy, the socio-cultural domain is subordinate to that of high culture; in the artistic field, it is associated with social work and pedagogy. Thus “Auf dem Sprung” does not operate within the same context as “Schulhausroman”. The fact that the exhibition venue, the individuals taking part and the artists and project initiators are positioned in the socio-cultural domain renders the project invisible in the art context. While both projects aspire to promote inclusion of excluded or disadvantaged groups and oppose existing → exclusions, the systems in which they do so are different. Although “Schulhausroman” taps into the debate about discrimination in the educational system and actively addresses it rather than merely mentioning it, the project’s primary aim is engagement with literature and positive experiences with writing. In pursuit of that aim, it acknowledges deficits in the literary domain with respect to its readership and attempts to engage with them through modes of cultural mediation by artists. In contrast, “Auf dem Sprung” explicitly places itself within the debate about migration and integration and sees art more as a tool to generate visibility for immigrant youth in a well-meaning context dominated by members of the majority. It uses this engagement to enable a selected group of these young people to experience a self-awareness which strengthens them.Omissions

Which questions of apparent relevance for an assessment of the project were left unanswered in its documentation? Certain questions arose during the analysis of the two projects for which the documentation supplied no answers. On the other hand, these omissions themselves provide information about the reflexivity of the project initiators, by indicating what it did not encompass. The documentation of the “Auf dem Sprung” project raised question which could only be answered through telephone interviews with the project director, Klaus Komatz, from the Archive of Youth Culture and author Anja Tuckermann.Auf dem Sprung: Project Initiation

What criteria did the teacher use to select participants? Anja Tuckermann and Klaus Komatz confirmed that the students were selected by the teacher from a personal point of view. The requirement of national origin was one of the key criteria, however the teacher deliberately disregarded it: two of the twelve adolescents were of German descent. The classroom performance of the students was not a deciding factor either: factors such as the level of motivation or the impression that certain students would benefit particularly from participation in such a project were of greater weight. This does not make the selection process any less problematic, since the selection involved a non-transparent experience of rewarding social behaviour and diagnosing need which suggested a pastoral/disciplining dimension. With respect to the composition of the group of immigrant adolescents, the project director and the author clearly disassociated themselves from reductive attributions when interviewed by telephone. Klaus Komatz said that the project had shown that the young people were ultimately Berlin youth, who were thinking about the same themes that other young people were. He added that the archive was not interested in “displaying the exotic”, pointing out that to some extent there is no such thing anymore.18 For her part, Anja Tuckermann insisted on recognition of the unequal opportunities and the fact that immigrant youth face a considerably more difficult situation than do members of the majority society. This discourse, gleaned from two telephone conversations alone, was directly triggered by the work on the project, and remained invisible in the representations of the project to the outside world.19 Moreover, at no point did the documentation make explicit reference to the fact that not all of the adolescents were from immigrant families. Had this detail been made transparent, the result would have been a considerably more nuanced and non-harmonizing look at the → issues of integration, particularly in the institutional context of “embracing diversity”. The project would have been able to deploy its potential with regard to these discrepancies – by, for example, including the young people in the debate about these issues.Implementation

How long did the collective work take place? The project gives the impression that the partnership existed over a longer term. Nowhere is it mentioned that the writing and photography workshop lasted only a single week. This fact significantly diminishes the project, by calling into question the coherence between the process and the output. To what degree is it appropriate to transpose a five-day engagement with literature and photography into a media-savvy travelling exhibition? According to Anja Tuckermann, the students did meet up again, for the readings, the fanzine workshop and the exhibition itself, but the actual work, which was presented in the various formats (readings, exhibition, publications) was created within the framework of a single week.Transparency

How was the project’s aim communicated to participants? Were the adolescents aware of the context in which the project work was taking place? The project participants were not confronted with the project’s aims or with those of the institution supporting it; they were only entrusted with the task of writing and taking pictures. From Anja Tuckermann’s perspective, this was primarily the result of a disassociation on her part with the initiative of the supporting institution. However, this omission within the context of the project prohibited engagement with the issues that contributed to that disassociation. According to Klaus Komatz, the young people did know about the context of the project, after all, he said “it was communicated in all of the publications [Internet site, flyer, etc.].” It was thus not possible to clarify definitively how well the young people were informed in advance.Level of participation

To what extent were the young people involved in the exhibition’s concept and design? To what extent could they influence/determine the selection of photographs/texts which were included in the different media? While the project director seemed initially uncertain about the question of the young people’s involvement, ultimately he said that they were involved “although it was difficult”. This information contradicts statements made by Anja Tuckermann, who said that she and the other artists involved were responsible for the exhibition’s design. Tuckermann then noted that the work with the adolescents did influence the design of the exhibition, meaning that they were indirectly involved. According to Tuckermann, photographer Jörg Metzner selected the photographs to be used. This decision was justified on the basis of relieving the adolescents from the difficultly of completing such a task without having the necessary experience. These statements are in stark incongruity with the project’s approach: the participatory orientation is cast aside at the decisive moment – active participation in design relating to self-representation and depiction – and the project falls back on the classic hierarchical structure. The omissions described above concentrate on two levels:- diverging interests of funding sources, project implementers, institution and project participants

- and the resulting lack of transparency with respect to the participants, objectives and level of participation.

Schulhausroman

Although the documentation of the “Schulhausroman” project is very extensive, it too leaves some questions unanswered. Therefore, the initiators of that project were also interviewed, generating information for this analysis not available in the generally accessible documentation of the project. Former participants of the project were interviewed as well, providing an additional perspective. How, specifically, was the writing process structured? The general organization of work in the schools is not clear: were hours devoted to instruction set aside for the project? Did normal instruction pick up on aspects of the project? How, specifically, was the collective work structured? What happened when conflicts arose during collective work? To what extent did the good students end up making decisions during the collective work process? The teachers were not directly involved in the process, but did engage in close exchange with the authors. This was particularly important when the writing process brought to light experiences of violence or other personal details, which required further action. The professional authors had the power to make decisions within the framework of the project and they determined the course and development of the project. The writing itself is not done solely by the students, it is created more through the oral stories told in the class, which the authors then put together in a text, which is then read aloud at the next session. All students participate in this process. Then they develop their protagonists further working in small groups. What criteria were used to select the students who read the texts at the literature institutions?

Schulhausroman reading at Literaturhaus Zürich, Photo: Iren Stehli

© Provinz GmbH Though it emphasizes that all students participated in the writing process, the project description does not clearly indicate which students participated in the readings held at literary centres or cultural institutions. According to former students, only a selection of the participants took part in the readings.20 The rationale for this is that several novels were read at a given event and thus more than one school involved. This raises the question of which criteria are used to select the readers. The reader-selection process could not be determined from interviews with former participants. Some of them suspected that a willingness to volunteer and a self-confident appearance were requirements. The described omissions for “Schulhausroman” can be summarized as follows:

- lack of documentation of the mediation processes on site and methodology and

- lack of transparency with respect to student participation in various phases of the project.

Conclusions

The discussion of the two projects highlight the fields of tensions generated at various levels in cultural mediation that is → participative in nature. These fields are also relevant for non-school contexts. The central question is always, who can benefit from a partnership and how? This applies in particular to projects which work with marginalized groups. The larger the knowledge and power gaps among the individuals involved, the greater the risk of → instrumentalization benefiting the institution or project initiators. Therefore, in order to transform rather than reproduce existing structural exclusions, it is essential that the interests of all concerned are analysed.Materials

The following material was available to aide in classifying and evaluating the projects: Schulhausroman- documentation on the → website

- published audio books and booklets containing the students’ texts

- interviews with project imitators Richard Reich and Gerda Wurzenberger

- email questions submitted to Richard Reich

- interviews with former project participants

- recordings of the readings in Theater Kanton Zürich, Winterthur, on Friday, 13 January 2012:

Auf dem Sprung

- “Auf dem Sprung” exhibition

- documentation on the → website

- texts and pictures of the adolescents

- film documentation of the project on DVD

- fanzine

- media reports

- telephone interviews with Klaus Komatz, the director of the Archive of Youth Cultures project “Migrantenjugendliche & Jugendkulturen” and author Anja Tuckermann, who led the writing workshop with her fellow author Guntram Weber.

- → report in Spiegel online, Schulspiegel

1 → http://www.culture-on-the-road.de/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=233&Itemid=106 [1.5.2010].

2“The interdisciplinary ‘Image Cultures’ working group takes questions of image studies which relate to the diversity of images and applies them to the diversity of the cultures which influence them. First image cultures are analyzed with respect to their depictions of space and perspective for their uniqueness and their claim to universal validity. The research of the working group is intended to focus in depth both on what makes a particular image culture special relative to others and what is universal with respect to a global image culture” Archive of Youth Cultures, Berlin: Image cultures → http://culture-on-the-road.de/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=253%3Ainterdisziplinaere-arbeitsgruppe-rbildkulturenl-&catid=1%3Aaktuelle-nachrichten&Itemid=1 [15.3.2013].

3 → http://www.jugendkulturen.de [20.10.2012].

4 The connections between educational background and cultural preferences are extensively discussed in Bourdieu 1982 and Bourdieu, Passeron 1990.

5 It is therefore essential for the project’s status that the authors work primarily as professional authors and are not primarily active in mediation projects.

6 → http://www.schulhausroman.de [19.5.2010]

7 Ernst Göhner Stiftung is a non-profit foundation endowed by the estate of the entrepreneur that funds both cultural and social projects. Stiftung Mercator Schweiz is a foundation founded by a German merchant family, whose funding activities include projects “initiated for better educational opportunities at schools and universities” which “stimulate the exchange between knowledge and culture for the purpose of tolerance”(→ http://www.stiftung-mercator.ch [20.8.2012]. See also Texts 6.4 and 6.7 in this publication).

8 → http://www.stiftung-mercator.ch/projekte/kinder-und-jugendliche/schulhausroman.html [20.10.2012].

9 → http:// www.schulhausroman.de [20.10.2012]; → http://www.schulhausroman.at 20.10.2012].

10 “As of 1 January 2007, the [German] Federal Ministry for Family Affairs, Senior Citizens, Women and Youth established the new federal programme ‘Vielfalt tut gut. Jugend für Vielfalt, Toleranz und Demokratie’ [Embracing Diversity: Young people for diversity, tolerance and democracy] to combat rightwing extremism, xenophobia and anti-Semitism and to support work in educational policy and pedagogy. A total of 19 million euros of federal funds are made available each year.” → http://www.vielfalt-tut-gut.de [20.10.2012].

11 The funding guidelines of the relevant bodies are posted on their websites: German federal programme “Vielfalt tut gut”: → http://www.vielfalt-tut-gut.de/content/index_ger.html [20.12.2012]; Senate Representative for Integration: → http://www.berlin.de/lb/intmig/aufgaben [20.12.2012]; Federal Ministry for Family Affairs, Senior Citizens, Women and Youth: → http://www.bmfsfj.de [18.11.2012]; Federal Agency for Civic Education: → http://www.bpb.de [18.11.2012].

12 Participative observation sessions would have had to take place within the project to permit a definitive judgement on this.

13 A fanzine, or zine, is a form of magazine first developed in the punk movement which is made by fans for fans within a particular scene. Fanzines are often handmade and consist of collages which are photocopied. The Archive of Youth Cultures possesses one of the largest collections of fanzines in the German-speaking world.

14 Klaus Komatz in a telephone interview with the authors [19.5.2010].

15 “SPI – the foundation Sozialpädagogisches Institut ‘Walter May’ – pursues the objectives of the German workers’ welfare institution and thus aspires to contribute to the development of a society in which all human beings can develop freely with responsibility for themselves and the community. The SPI concentrates primarily on the living situations of the people concerned, focusing its social work particularly on helping individuals to help themselves.” → http://www.stiftung-spi.de [20.12.2012].

“‘Ostkreuz’ is the SPI Berlin foundation’s mobile counselling team for democracy development, human rights and integration. Since its establishment, it has focused chiefly on shaping social cohesion in the pluralistic city of immigration Berlin and on opposing ideologies and campaigns which make claims of inequality or dissimilarity of people based on group affiliations.” → stiftung-spi.de/ostkreuz/ [20.12.2012].

16 → http://culture-on-the-road.blogspot.com/2009/05/workshop-islamische-und-islamistische.html [20.10.2012].

17 Hermann Glaser, a German expert in communications studies, author and professor, studied German cultural history in great depth.

18 Klaus Komatz, in a telephone interview with the author [19.5.2010].

19 Both Spiegel online and Zeit online reported on the project, publishing photographs and text passages. However they stayed on the level of attributes and reductive visions defined by ethnically and nationally affiliations. → http://www.zeit.de/online/2009/18/bg-aufdemsprung; → http://www.spiegel.de/schulspiegel/leben/0,1518,621642,00.html [20.5.2010].

20 Interviews with former students of the Erzbachtal School in Erlinsbach, CH, were conducted in October of 2011.